Mindful Practices: Brian Jerome

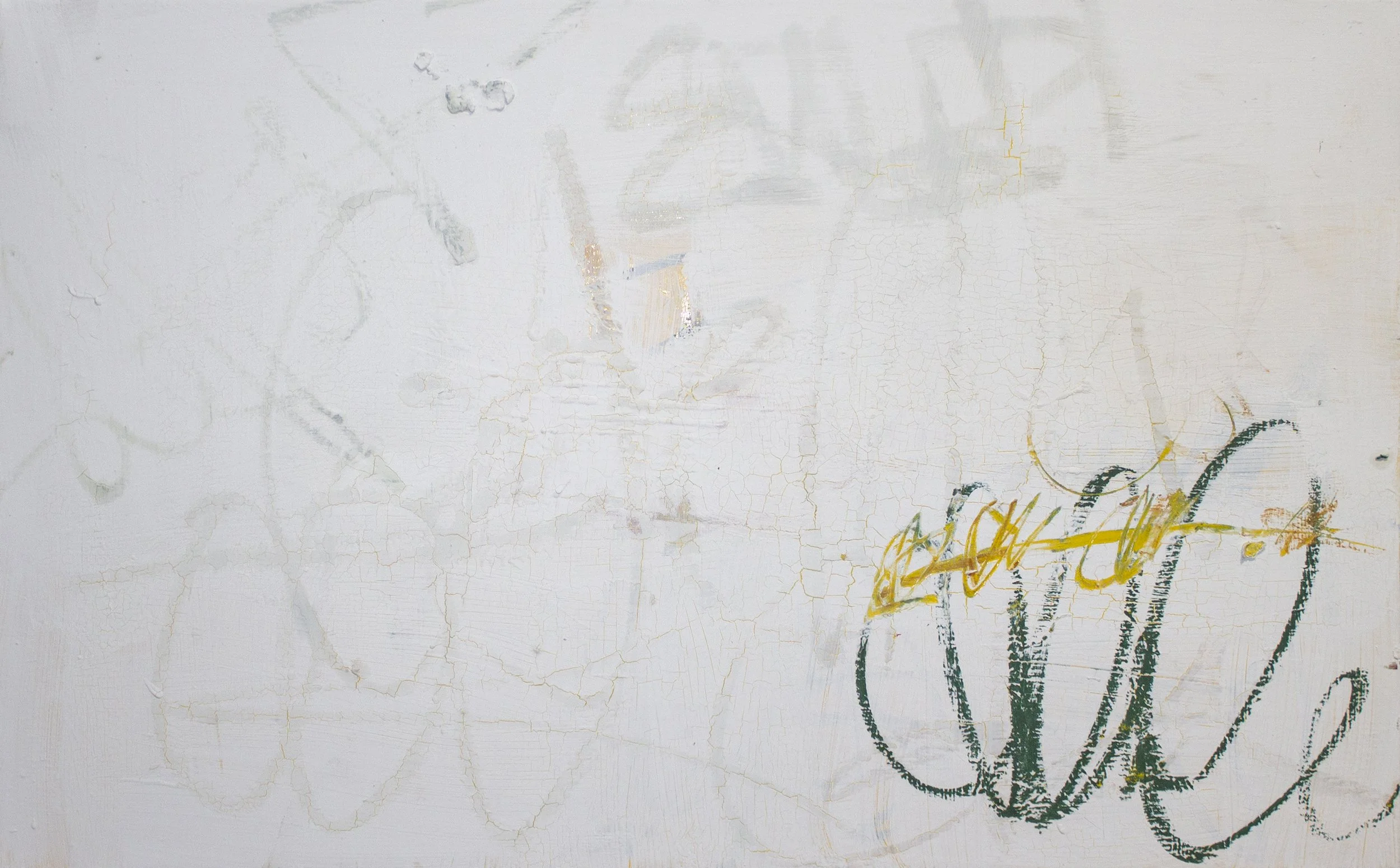

Gradually It Became Unclear, Both Involuntary and Unconscious, 2023

Oil, acrylic, graphite, litho crayon, oil stick, graphite, colored pencil on canvas

62 x 34 in.

I do not consider my work to be about trauma, but it is based around it. I do consider my work to be about life and about my experience as a human. It is an abstract, diaristic approach to talk about the things I find difficult to be vulnerable about.

In 2010, I fell 5 stories through an abandoned building and was left in a medically induced coma for 10 days. I woke up to learn that I almost died, my femurs were broken, and the last 10 days of memory I had were all hallucinations. That experience resulted in complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder with previously diagnosed Bipolar II disorder.

I found abstraction as a way to comfort and deal with these things. I found painting and mixed media as a mindful approach to deal with overwhelming thoughts. I know it is not just me that has gone through the confusing nature of life. In fact, I know I am lucky to not have suffered as hard as others have.

However, I cannot shake the fact that we all deal with these atrocities that surround us, no matter how small or large. The hopes of my work are not just to serve as my diaries and therapy, but to allow for a discussion for each and everyone of us to admit that things are hard, and even harder to explain.

Rendement, 2023

Oil, sign paint, acrylic, oil pastel, graphite on canvas.

20 x 32 in.

Welcome Brian, can you introduce yourself?

My name is Brian Jerome. I'm an artist that up until four years ago was living and working in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. I still work there, but I moved outside with my family. I work out of Philadelphia, that's where my studio is.

I went to undergrad at Tyler School of Art at Temple University where I focused on printmaking as a means to become an illustrator without doing the graphic design program. At that point, I didn't have the discipline to do graphic design and I found printmaking to be kind of more open-ended and process-based.

And then, I was fortunate enough that the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts reached out to me and asked me to attend graduate school there, which I did. And it was there that I transitioned into becoming a mixed media painter.

You began your career as an illustrator, primarily working in printmaking. What made you pursue painting instead, and who/what were some of your influences that informed your definition of abstraction?

Living in Philadelphia and going to the PMA (Philadelphia Museum of Art) to see Cy Twombly’s “Fifty Days at Ilium” when I was in high school—I grew up in York, Pennsylvania, which doesn't really have an arts community at all, but I was fortunate enough that my high school teacher made a trip to Philadelphia to see specifically this exhibit for me. I was kind of like a worrisome student, and she noticed that art was a really good focus for me and a positive thing. So, she was reaching out trying to get my angst to turn into art.

And I actually hated the exhibit. When I first went, I had a really clear definition in my head of what art should be. And to me it was really defined by my love of comic books growing up. I really enjoyed Ralph Stedman's illustrations, and I guess, especially when I was younger, things had to have like a sense of violence to them, or a sense of urgency, and sense of fear.

As I progressed more, and through drawing and illustrating, I slowly moved into being interested in abstraction, because I realized you can only portray certain emotions and thoughts to an extent representationally. After that it doesn't really get the message across. So, it took me ten years, give or take, to realize that what I wanted to communicate was innately abstract and I had to find a different way of doing it. And in doing so, I initially thought of the Twombly room—and I visited there, and slowly branched off to visit other forms of abstractions.

Before graduate school, my grandmother purchased a newly published Rothko biography book. And in reading through his life—I had only grown-up seeing Rothko’s in books where you can't really see the gravity of the painting and really have that experience Rothko wanted you to have of being smaller than the painting and being aware of something larger than yourself. And that really changed my mind on what artwork could do.

In my own practice, the up-close interaction is very specific to the viewer. Because in this day and age of technology, you just simply can't take a picture of how light affects an object and subtitles behind it, especially if you're using a multitude of different whites.

Abstraction took me a while to get to. And I didn't know until I went to graduate school that I was considered, by some professors and some of my peers, “too young” to do abstraction. At that point I was twenty-five turning twenty-six. And I kind of understand that in hindsight, but I would still tell anybody, ‘as long as you have your chops and you've lived enough life, you can probably go into abstraction.’ If you don't feel like you have a real complex thought on what being human is or witnessing life, I would tend to say, ‘focus on something else before you find abstraction.’

Can you say more on how someone can be considered too young to be an abstract artist?

I personally take it more as it shouldn't be an ageist thing. I don't think that there's an age for it [abstraction], but I do think that there's a maturity in work that has to happen. At least—and this is all opinion—but I would say, depending on the kind of abstraction like pattern, design, geometric abstraction can come at an early age and there's a place for it in the world, and it can be fine arts. But I would say, especially with minimal abstraction, I feel like you should go through a huge growth period of trying so many different styles and almost going over of what's too much in a work of art to bring it back to the core of what you think needs to be in there.

And you might be an artist that really overloads everything, that might be the answer too. But I think it's really important in your career to not just be eighteen and go to college and think that that's the artist that you're going to be for the next fifty years.

Again, with the aging and everything, is I have to search through thirty-three years of my life and filter things, to get things out. And I feel like if I was still sixteen, I'm only building things off of the prior sixteen years, which usually aren't that insane in the scope of life as you get older. So, you're only working with a limited sense of emotions, and even traumas, that I feel like as you go through life there's more things to pull from when you're a non-representational artist because you're almost searching for more and more things.

I have an anecdote. I remember I had a couple of professors in grad school, and one very, very great one in undergrad that always talked about THE paint and the feeling of THE paint. You think your professors are nuts using these terms and stuff, but as you get older, you understand what they're saying because they're even abstract terms. It's not the paint as in the object, it's almost like the paint as the universal creation of painting, and what that artistic creativity can do with material.

And so, I had these professors constantly telling me like, ‘you gotta feel the paint.’ And I thought that they were nuts! And it's actually—at least from what I found—this falling in love with yourself, the materials into the creation, and actually being a part of it and not separating yourself from the object.

And sometimes things like white on white become very special and romantic in that thing, because almost you, as a creator, are the only one that knows that moment in it. And you kind of really hope that that moment it's seen by somebody else as being that delicate or that, at least for me, intentional.

The Spoils of (Civilized) War, 2023

Oil, acrylic, graphite, pastel, oil pastel, colored pencil and lithography crayon on canvas.

38 x 62 in.

Pieces of Peace With No Peace of Mind, 2022

Oil, acrylic, colored pencil, chalk pastel, oil pastel, crayon, graphite, charcoal on canvas.

50 x 44 in.

We Waited While It Approached, Whispering, 2022

Oil, acrylic, colored pencil, chalk pastel, oil pastel, crayon, graphite, charcoal on canvas.

56 x 50 in.

Too Much, Too Late (Mania), 2022

Oil, acrylic, colored pencil, chalk pastel, oil pastel, crayon, graphite, charcoal on canvas.

60 x 46 in.

You describe your work as a diary. Can you explain what that process means to you and how it is translated externally?

Yeah, that's a good question.

The first part would be me and the paint, and the object and going through my life. So, I'm a pretty vocal person—an open person—so I have one way of coping and processing. Which I'm, assuming to a lot of people seems very healthy that I can talk about my feelings and everything. But at least for me, that is only so much an extent of what I mean. Because a lot of it [my artwork] is extremely emotional. If you think about it, ever since you're growing up from being a baby, you're just slowly translating cries and screams into explaining what you mean.

So, the personal things to me, I'm thinking about them, I'm interacting with them, I'm processing them while I make the work. It's the definition of cathartic. And it's a huge release for me. And the age-old question on when a painting is done, for me, is when I have processed what I wanted to do, and that can be a whole spectrum of emotions and everything. And it's when I feel like I have nothing more to say, even though I’m not talking. And sometimes, you know, it's not resolved so the painting might be wonky, and might be off a little bit but that's the end of me dealing with it. And I have to accept it as a human that events take place and feelings take place. So, in turn I’m sharing that with the painting, that even if it's unresolved, it's okay. It still exists.

And then the interpretation on a second fold is from the viewer and the object. And I typically find it more interesting to not originally be there when somebody is viewing a painting, because I feel like naturally, me being there tends to skew it because the first question that somebody asks is like, ‘what were you thinking, what's this piece about?’ And because of what I said, what my work is about, is I don't want to talk about it. That's not what's important to me. It's important that I put it [my artwork'] out there in the world. That's me dealing with it [my process]. And my hope is there’s something in there [a painting] that the viewer can find some interconnection with themselves.

And typically, I found that people tend to say, ‘I don't know why, but I just love this painting or this area,’ and I don't think that they have to tell me anymore, or to find anybody else what they like about it. Because to them they're having that connection of what you can’t speak about, and that's pretty amazing.

Can you expand more on how you image the viewer engaging with your paintings considering how vulnerable and intimate a diary is? Is the literal dialogue happening between the viewer and the title of artwork?

That's a really good question that I should ask myself.

I would say it's such a weird second or third thought in my head. Before I publish any painting—which I guess is now another form of processes—is I get to decide when people see these, and that's also when I complete the thought.

But sometimes they go weeks without titles because I want the title to fit the emotion. It's the closest word I can get to encompassing the entire feeling of it.

And I guess I do that because I was never a fan of ‘untitling’ things, or if I ever have a painting called “Untitled” that would be for a specific reason. So, I find those [titles] to sum them [the artwork] up, and then I guess that's a kind lead in for a viewer, for abstraction.

I've been told that the titles really help somebody, because it helps them believe if people are tied to seeing imagery. It can help them start seeing something to process it.

With the titles, I try to use vague pronouns and sometimes collective pronouns as a way that—even though it's personal to me, if I’m sharing it with somebody else, I can't say, ‘me, me, me, me, me’ all the time. Because then nobody cares, and it's annoying. So, I do try to invite the audience with me, that they are a part of it with me, while they share it.

So, yes, it's two-fold. The titles are there for me as an attempt to explain myself, but it's also there for the interpretation for the viewer.

I want to circle back on something you said earlier about responding to urgency or immediacy. How does one respond to urgency/immediacy to create a work of art, and how are you trying to define that?

I live half hour to forty-five minutes from my studio, so if I have an immediate idea or a certain color or mark-making comes to me, I either have to write it down here in my house and hope that I understand it by the time I get to the studio. Or, I have materials here that I can try and do that with. Or if I’m fortunate enough, I just bolt right to the studio to do it.

That's why, at my studio, sometimes I’m just sitting there for hours listening to music and looking at work that I’m working on, because there is a layering in my work that even though I work over layers and stuff, I personally feel like I can still screw it up. If I’m having this one beautiful moment in one section and I really go all in with a graphic mark, I’m losing that. At the same time, that's part of my practice to overcome those things and understand tangibility. But sometimes it's a super big bummer.

So, I sit there meditating, taking a long time to come up with something that sometimes the mark is done in milliseconds. Then I’m back to sitting again. So, that's also one of those questions when somebody asks, ‘how long does a painting take me?’ Because there's aspects of my paintings that people can read quickly and aspects of people can read slowly, and I think that that's a cool conversation for a piece to have. Because it was drawn out for a split second, kind of like moments in our life. We can have weeks of boringness and shittiness, and then there's like one good announcement you get. Both things are real, and one shouldn't take precedence over the other one, really, because they live symbiotically.

I Wrote Letters; I Tried to Build a Story, 2022

Oil, acrylic, colored pencil, chalk pastel, oil pastel, crayon, graphite, charcoal on canvas.

48 x 60 in.

An Answer So Clear It Could Barely Be Recognized, 2023

Oil, acrylic, graphite, pastel, crayon on canvas.

28 x 44 in.

In your artist statement, you write about a traumatic experience you’ve had and how you use art as a way of healing. What advice, if any, would you share with artists to create a practice of care?

I think having the right time of alone time can really help to process things. Because you are left by yourself, and you're kind of forced to process things. Or even if you're trying to push them down, your brain's gonna have you have it come out of you in some way or another, and that's definitely better than bottling it up inside. I think art can also help, like with me, to express things that you might not be comfortable expressing to other people. And just like I do, sometimes, there's still a veil to it and a protectiveness to it. But it's still a step towards vulnerability.

I have friends down to my studio a lot, and it takes us back to college that we used to make art together. And these are all pieces that aren't for sale, a lot of times they go on the trash afterwards because it's just hanging out critiquing and doing that. But most of my friends, especially from undergrad, we were a group of people that we didn't take things overly seriously, but in turn, made us very serious artists. If one of my friends goes ‘oh, I love this area, but that over there, that just sucks.’ I'm not going to be offended, because then it's up to me to defend if it sucks or not, or maybe it does suck. But at least we're having a conversation between two people, and it kind of takes you out of that polar opposite of spending time with yourself. I think a studio practice is both personal and it should be a place where others are involved also.

I really think everybody should have a creative outlet, and I feel like sometimes people feel like it's a closed world in creativity or very exclusive, and it's not. I love hearing that since the pandemic, some people have just picked up something creative as a hobby, and I feel like that would be so much more beneficial to our society. I had a friend in undergrad do it—you can be a baseball player, and you can still do ceramics. Like, you don't have to be all in on one hobby or the other.

Even though a studio can be a sacred place to a person, if you're invited inside it's not a church. So, people come in feeling like they have to have gloves on or be delicate. And at least for me, it's an extension of a home. And, so, I welcome people in.

Usually collectors are the ones that asked to come [to my studio], but I really try to always say, ‘yo, you should come out to my studio,’ and I hope nobody ever takes it as like, ‘Oh, you gotta check out my studio.’ It's just that I like providing a space where others can create also because that just makes me happy, you know. To share that experience with somebody else.

And not everybody has the resources for a studio or resources for a bunch of materials. I didn't for an extremely long time, so I like sharing that. And other people that have the means to a studio, I call to them to invite more people to come do work with them in the studio.

You are also a chef. Does the labor-intensive process of cooking inform your painting practice in anyway?

I consider cooking to be kind of like my sculpture practice that some other people have. It just happens to smell and taste really good.

But I accidentally became a chef from starting as a dishwasher while I was in high school. But anybody will tell you, unless you're lucky enough to have the privilege that you don't have to work as an artist, you typically end up in the food industry. And in all humbleness, I ended up being really good at it [cooking]. And I do think that that comes from an art background because of how I think about food.

White wine and seafood to me is like Naples yellow and adding some white to get a perfect egg-shell. It’s theory, but it's also trusting yourself and it's also what works overtime. And you can create style in a kitchen, too.

The interesting thing that doesn't fold over between the two is, I'm very, very, very clean in a kitchen and well disciplined, but my studio is a wreck. It [my studio] has like four different stations. I'm constantly moving materials over. And, I guess, another thing that being a chef informed my work is, I change out when I go into the studio. I used to wear the same street clothes into the studio, but I kinda look like a hot piece of shit all the time. So, having different clothes, I feel like makes me more appropriate when I go into public with my wife and stuff.

There's a mindfulness of being a chef that is very similar to the mindfulness of being in art. The only difference is the mindfulness of being a chef, there's still a sense of stress and immediacy where I feel like the timing of painting can be a lot more slowed down. But it is a similar experience because you're making something.

Who I Was, Where You Wanted to Be, 2022

Oil, acrylic, colored pencil, chalk pastel, oil pastel, crayon, graphite, charcoal on canvas.

52 x 26 in.

How do you know when a painting is done versus a dish? Do those same rules apply?

I would say at first, even over cooking or under cooking something is one aspect of cooking. I would say the overlap between the two really happens when you have a chef or somebody that over complicates a dish. And I think that typically comes out of distrust for yourself that sometimes over complications can be over seasoning. Less is more when it comes to food, typically. And I believe, a lot of the times, is the answer for art. It just takes artists a long time to realize what their bare bones as them themselves, as the artists are.

It's really actually weird because you have more ability with a dish. There's a visual sense, an olfactory sense, and a taste sense. So, you have more chances of hitting what you want on an initial try. You can get one of those three correct. Where a painting, you're really only working visually—and I guess emotionally—if that's a sixth sense, but that one's a wild card.

So, when I’m done with a painting, is when I have nothing left to say about it anymore. And the weirdest thing ever, is typically there's some that are unresolved and they drive me insane. But even in my brain is like, ‘maybe a painting down the road will help me resolve that, but I’m done now, and I have to move on because you can't ruminate.’ And so, that's when I’ll take them off the wall—and tying into printmaking—I lay them flat and put the stretcher over it. So, like a print

going through a press, I have to really hope that it's gonna look like what I want, when I pick it up off the ground. But then, that's the final idea. And then I document it and title it. And really, when the title goes with it, that's when it's completely done.

And interestingly enough, the paintings that I don't find successful, but yet again are finished typically, sell first, and it's kind of frustrating. I guess there's more of a connection there if more people feel unsettled and unresolved also.

Maybe that is a cool, shared feeling to have.

Have you had any feedback from someone who's purchased your work that might answer that in anyway?

With any purchase, I used to put in a little note that I thought was really nice—and I hate the word, but a little cute. I'd say, ‘Thank you for buying it [the artwork]. If you have any questions, please contact me. I would love to tell you more about this work. And can you show me an installation shot.’ I think I've gotten two people that ever did that at all.

Weirdly enough I feel like there's an aspect of buying my work that might be private. If they're having a reaction like I intend to, maybe they don't want to talk about it either. And I've been lucky enough to see some of my work that has been displayed in the middle of a living room. I've had a painting put in somebody's bedroom as a centerpiece, and that one's kind of an honor because that's somebody's private room. And that's something that they're looking at every morning when they wake up, and the last thing before they go to bed. And that's pretty incredible.

Do you have any final thoughts or announcements you would like to share?

Yeah, I have a show at a gallery in Miami called Galeria Azur. And I have no idea what to expect, and I've never been to Miami, so we'll see how it goes!

Always (&forever), 2022

Oil, acrylic, pastel, oil stick, colored pencil, graphite, chalk on canvas.

36 x 60 in.

About Brian Jerome

Brian Jerome was born in York, Pennsylvania in 1990. He was raised in Dallastown, Pennsylvania next to a corn field. He moved to Philadelphia in 2008 to pursue and receive a BFA in Printmaking with double minor in Philosophy and Art History.

In 2017, he was awarded his MFA from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts on merit scholarship. Brian has been shown and collected all around the world including the United States, Canada, Mexico, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain and the UK.

When not in the studio, Jerome spends time with his wife and 3 daughters or cooking as a professional chef.

He loves gold.

Website: www.brianjerome.com

Instagram: @brianjerome_