Anxiety Is A Love I Cannot Break Up With: Juliet Martin

Never-ending, 2023

Hand-woven fabric, inkjet prints, machine-made and hand-spun yarn, glitter, wood block

5” x 5” x 2”

Anxiety is a love I cannot break up with.

Using traditional techniques of weaving and drawing, I create sculptural pieces infused with the language of love, loss, and anxiety. My discordant tapestries are fiber memoirs. These highly textured works combine many sources of materials: drawings, hand- and machine-woven fabrics, banners of text, wooden blocks and, most important, glitter. My love of fiber and illustration as both a technique and a symbolic presence imbues these emotional, often humorous pieces.

Spin, weave, draw, write. Woven and machine-made fabrics are attached to wooden blocks, wrapping a present. Sketches and textual ribbons are edited in Photoshop, personal emojis strung together to communicate my relationship with anxiety. Angels are guardians. Horses are strength. Ribs are protection. Insects are agitation. Each three-dimensional piece is further glitteringly dressed on its top and sides, creating sculptural wall hangings.

My relationship with my process is always intimate, as emphasized by these especially small works. My insecurity invokes my detail-oriented process and opens myself to my audience. I can’t help tell a story any other way. You cannot see that I spin and dye much of my own yarn, but even that helps tell the tale. Weaving becomes my noun and my verb. The simple design of my loom encourages improvisation and even mistakes. Drawings and writing illustrate my vulnerability. The compositions are as much poetry as artwork.

My mental illness manifests mostly as anxiety. My bipolar disorder, diagnosed 35 years ago, has taken many forms over the years, now especially as panic attacks. People say to me “You don’t look crazy,” so I want to show how chemical-driven anxiety can dominate everyday life and love.

Welcome Juliet, can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Yeah! My name is Juliet Martin, and I live in Brooklyn with my husband and my cat.

About 25 years ago, I worked as a digital artist and was very active in academia. Now I'm a fiber artist and I combine weaving, drawing, sewing, dyeing, spinning into fabric sculptures that I call fiber memoirs.

My work is about things I'm going through or thinking about going through. For example, I did a collection called ‘Household Items Remind Me of You’ about what would happen if COVID caused me to lose my partner? A curator actually gave me condolences about my loss. And I was like, ‘Oh, shit.’ And so, I had to explain to her that it was about loss and not loss itself.

So, I sort of say that my things are not always real, but they're always true.

You combine technology and weaving in your artwork. Both practices follow rules, such binary code to the choice of weaving patterns. Can you share how that interest came about?

I did have a set of rules for myself when I was programming, but that was sort of the nature of the process. You can't have a typo in your code or it just won't work. It's one, it's zero, no maybes. But, with weaving I actually do not use patterns and instead I use and break different kind of rules in my work.

For example, limiting my palette is how I start every project. I choose about four or five colors that are close in range, like a collection of blues. I choose an accent like a screaming yellow, and it's all intended to sort of to look like a natural progression. I would say the closest to patterns would be repetitions. It has a loose structure and accents the entirely free form weaving I usually do. Ironically, the free form weaving is done really deliberately. I make very clear decisions to make things look improvised. So, in a way, the rules are meant to look like there are no rules.

Endlessly Evasive, 2023

Machine-made fabric, inkjet prints, glitter, wood block

6” x 6” x 2”

What are you hoping to learn or find when giving yourself these rigid guidelines to work within?

Both in digital work and in weaving, I want the viewer to know what I'm doing. I want them to see the keystrokes. I want them to see the loose threads. I want them to understand the medium. I feel like it brings them to be part of the plan, sort of like, in on the joke.

As an example of limitations, in my digital work, the first was I was making art based websites, so they had to be seen on a screen. And that starts with a structure. The viewer is at their computer, a very conscious decision and different from a museum. The hardware was the starting point. Looking at the screen became the first step. Type in your web address and that becomes your title. So, that was a very rigid process for myself as well as the viewer.

Weaving is my backdrop and my focal point. When I start a collection, it's very hard for me to weave something that isn't emotional, but as I said, the process does have rules. I want to discuss the drawings in my recent works because that actually is a very structured process. The drawings of my last two collections were very deliberate for a collection called ‘I See You Falling Out of Love With Me.’ I created two groups of puzzle pieces, one was about five or six drawings of falling headless bodies, and the other was a collection of animal skulls. So, for each piece, I would combine these parts like a falling body in a red dress with a buzzard. And then I worked those into a woven background.

And the collection we're talking about right now I have groups of horses and birds and angels. So, with all this, I mix and match these things almost like emojis to send a message with a subtle—less mysterious language. This mix and match forces a structure which drives me to create and recreate a message. So, I have to be very careful that things don't become formulaic.

All this helps me put together a cohesive collection and it gives me something to push against creatively as well.

Fever, 2023

Hand-woven and machine-made fabric, inkjet prints, machine-made and hand-spun yarn, wood block

4” x 4” x 1.5”

Horse, 2023

Hand-woven fabric, inkjet prints, machine-made and hand-spun yarn, glitter, wood block

4” x 4” x 1.5”

You taught for many years, even founding digital art programs at prestigious schools like Parsons. Why digital art? And what did you envision technology doing for the art world?

I was born into computers. Both of my parents were computer programmers, so it was in my home when I was growing up. I remember playing Pong when it was first developed. I we sort of joked that the first computer art I did was drawing on punch cards that my parents brought home from work.

After majoring in art, in college, my mom showed me a CD-ROM which were just showing up on the marketplace and you could click on a bunny and it would hop across the screen. And that blew my mind. I was like, this is what I want to do. I want to make art pieces like this. So, I applied to every digital art grad program I could find. All eight of them, and ended up studying at the School of Visual Arts.

So, when I started teaching, it was really essential to put together a program that could bring people, you know, at that point students were coming from high school having barely used Photoshop, if ever. And they sort of had this image of what digital art would be like, which was great, but we had to put together a structure that would guide them technically, but more importantly, conceptually.

So, for example, we had a starting freshman class in the new digital program was divided into three groups and they each had a professor. I had my group of 10 students. And each professor taught their version of interface design (creating a portal that someone can use to accomplish a goal or a purchase). So, then when the students were all together, they all had different views on what you could do with regard to interface design. Some people were more theoretical, some people were more practical, but we really had to think about what is the best way to do both things. Like, we want people to understand the ideas as well as understanding the technology.

In my mind, technology really recontextualizes art. It's like taking a can opener to play the violin, which Laurie Anderson probably did. But, in a way, I really came late to the game. 60s artists like Nam June Paik and Lillian Schwartz, they really took something considered to be cold and calculating and used it to explore concepts and compositions and emotions. You know, they were really asking the question what could technology do for the art world?

I think, for myself, I saw it as a way to literally interact with the audience. It opened up possibilities to bring the viewer into the art piece. I remember seeing one of Gary Hill’s video installations, ‘Tall Ships’ where you walk into a dark hallway and there are videos of men sitting on the ground and as you walk by them, they stand up, walk towards you, look you up and down, and then walk back and sit down. And the whole thing was triggered by the viewer's movements. And for me, that sort of relationship is a great example of where things are going.

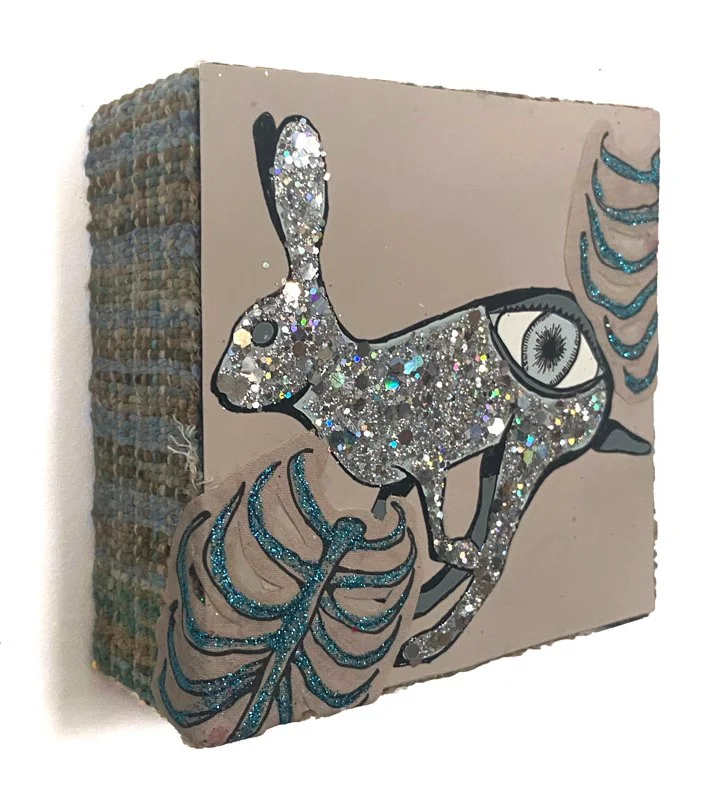

Rabbit, 2023

Hand-woven fabric, inkjet prints, machine-made and hand-spun yarn, glitter, wood block

4” x 4” x 1.5”

Having a background in interface and user design, does that appear or influence your weaving practice in anyway?

Talking about digital art, there was a hypertext website that I put together called ‘OOOXXXOOO’ and it was a combination of ASCII design with poetry I'd written. It was very important to me that the viewer could go through this and experience it in a way that they were sort of trained to experience a consumer website. Before they would see mine, they would be exposed to Google. So, they already sort of have this language of how to get through a commercial website. And to take that and sort of put in its place an art based website. It was almost like a stepping stone. So, that you had this vocabulary and now I'm going to sort of turn it around and use that to convey an art piece.

Fiber art has developed enough now that people aren’t looking at it and misunderstanding it for craft so much as they did before. Now there is that language out there and I can do a tapestry that's an art piece and people aren't looking at it as just something that would be used for a purpose.

I did a collection called ‘I Would Wear That’ because I kept weaving things and people would say, ‘Oh, is that a scarf? Oh is that a sweater?’ And I would say, ‘No, it's an art piece’ and they'd say, ‘Well, it could be a scarf.’ And I'd say, ‘No.’ And so I made a bunch of pieces that were very aesthetically driven, which was sort of different for me, and called it ‘I Would Wear That.’

You describe this body of work as a mythology of anxiety. Can you share more on what that means?

About five years ago, I did a collection called ‘You Don't Look Crazy’ which was about my history with mental illness. And a couple months ago, I had said to a friend that I really wanted to do a new work approaching different sides of mental health, but at the same time I love to talk about relationships. And, literally right then, it occurred to me that the longest relationship I've ever had is with anxiety.

I don't think anxiety is a good or bad thing. It terrorizes us. It motivates us. I don't know what I would do without it. So these ideas are not spelled out exactly, and that's intentional. I've made little building blocks and paired them with words of dismay and uncomfortable images. They may not make you anxious so much, but hopefully they'll make you think about it. And that's where the title becomes important, because it sort of gives a push in a certain direction. Almost like, you know, a one sentence cliff notes.

A mythology traditionally contains an obstacle and resolution. By channeling your emotions into art making, do you see yourself reclaiming anxiety?

There's not necessarily a beginning, middle, and like resolve that it's more of exploring just this feeling. And, hopefully, the journey would be to accept your own anxiety and that's where these little pieces come in, because they sort of put it into a funny context. They put it into a weird, you know, arrangement.

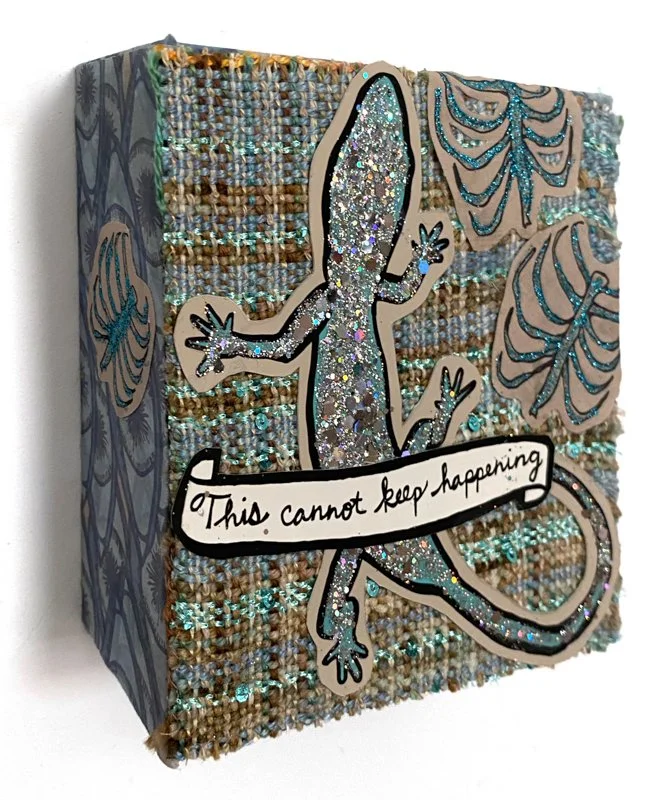

This Cannot Keep Happening, 2023

Hand-woven fabric, inkjet prints, machine-made and hand-spun yarn, glitter, wood block

5” x 5” x 2”

Was this series a battle to complete or were there elements that were fun?

Yes, I would say every time I start a new collection it is a battle. I tend to call it weaving purgatory. I don't know what I'm doing. My ideas tend to be terrible. Compositions are predictable. I hate everything. I hate everyone. I hate myself.

But once I finally figure out what I want to say, it becomes fun. Now, obviously the anxiety is a painful place to be and when I was deep in creating these pieces, I was experiencing a lot of anxiety within my life. So that made me uncomfortable. But then to make these pieces, it became almost like this fun benefit of the anxiety. And the anxiety is there, so why not do something with it that is a little more fun, a little bit more of a satire of how it is and how you're feeling.

How do you envision others engaging with your work—specifically this series? What do you want the artwork to say?

Well, the collection I'm talking about right now is called ‘Anxiety Is A Love I Cannot Break Up With.’ I know everybody has anxiety. Hopefully seeing it in this more playful and disturbing context it will allow people to appreciate their anxiety as something more than a flaw. It also gives a peek into my own neuroses and so, maybe they get to know me better, which is something I feel like a lot of artists want. They want their audience to see them, to see how my brain works, and maybe how the audience's brain works too. In a way, I use myself as a springboard for bigger issues and I want those vulnerabilities to make people a little uncomfortable and maybe laugh a little.

With each collection I make, at the opening there's almost always one person who really gets it. At my last opening, a girl, she approached me in tears saying that I had made her not feel alone and made her feel understood. And that's everything. I mean, that's why I make art.

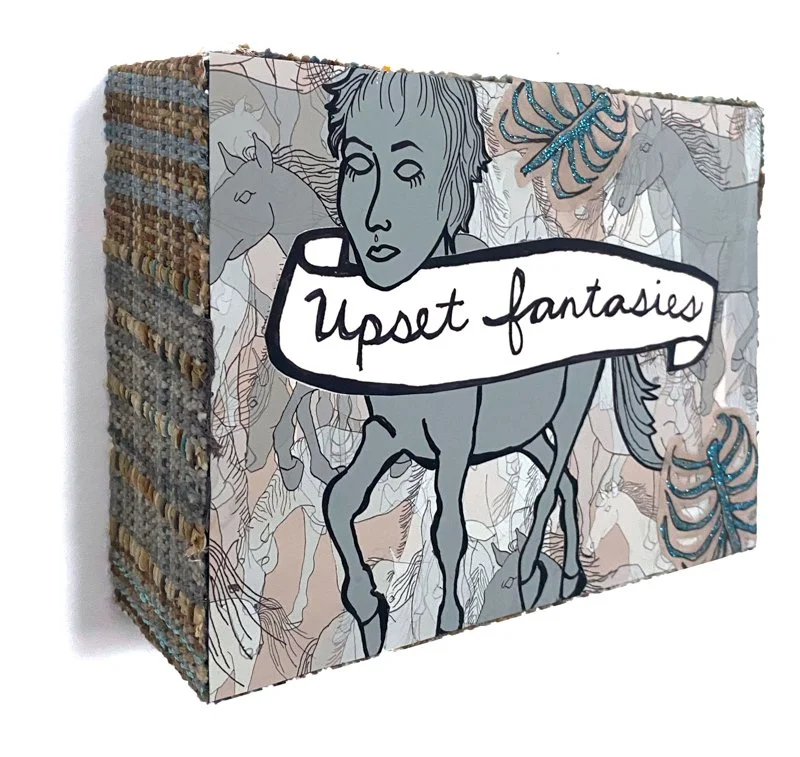

Upset Fantasies, 2023

Hand-woven and machine-made fabric, inkjet prints, machine-made and hand-spun yarn, glitter, wood block

6” x 8” x 2”

With the advancements of technology and weaving, how has your practice changed over the years?

When I was doing digital work, I did art based websites and mostly text driven technology. At that point, the Internet was growing at lightning pace and things were getting more and more flashy. And so, for me, when that was going on I tried to challenge that use of primitive versions of websites. I made a lot of ASCII art and I did pixelated images. Now, with regard to the work I do with tools that I use for my images are really what technology has influenced. I use Google to find my images. I use Photoshop's continually updating interface to create my drawings. I use my printer to transfer my images onto fabric. I just started drawing on a tablet using this amazing app that makes drawing on an iPad almost an analog process.

In terms of weaving, there is a loom that I use that is incredibly important to my practice. It's called Saori weaving. It was developed in Japan relatively recently, about 50 years ago. It rejected patterns and counting in weaving. You know, in traditional weaving you might do a twill pattern, and this is very different than that. The loom has two pedals, as compared to six or more on a traditional loom and it's entire philosophy is that there are no mistakes and you are encouraged to weave as wildly as you can and do what feels right. You know, stick some ribbon in there, keep the loose threads of these ideas influence the physical way that I work and the mental process of when I am weaving.

Is there a tool or equipment that is essential or is consistent to your practice?

I would say writing. I know that's not a tool so much so, but writing is very important to me and using language in my pieces I always come back to that.

I did some work for a while that didn't have text, but it was always accompanied by a very explicit title. The title became so important. But when I was doing digital work, it always involved writing prose, fiction, and then when I moved over to weaving and I started to really find my voice within that medium. I started using writing in my pieces in all different sorts of ways. In earlier pieces the writing became the texture. I would have an image of a sofa and there be writing all over the upholstery. So in a way, the writing became the pattern for that fabric. Now, in this current collection I have sort of these banners using text to pump up the message of the pieces.

So I would say, you know, the tool for me is really the writing.

Writing is also literal. How much influence do you want to have with your viewer on how they should be engaging with the work?

I would say that I'm trying to give them a push in the right direction, almost like a subtitle in a foreign movie. You know, you see the piece and let's say you have one reaction, but at the same time, you just see. So, at the same time you're seeing the text and you're seeing the image and in a way, they're sort of bouncing back and forth off each other. So, it's a pathway to the image.

You Haunt My Imagination, 2023

Machine-made fabric, inkjet prints, glitter, sequins, wood block

4” x 4” x 1.5”

Historically, weaving has been associated with domestic work where computer science is largely male dominated. Is that something you think about, and do you see your practice disrupting those gender norms?

When I was doing digital work, I was running around all the time saying, ‘I'm a woman, look at me, I'm a woman on a computer.’ You know, I was the only woman in my programming class at grad school, and it was very important to me to bring attention to my gender. I wanted people to know that I was part of this, and not that that was OK, but that it was happening.

Now working in a medium that is primarily dominated by women, although that's changing very rapidly, I think it's really important to discuss the transformation of women's work as craft into fine art, and that women play a role in that. Miriam Schapiro really had a role in that, taking materials of craft like lace or gingham or quilting and brought that into fine art. And that, I think, is very important.

I can't escape my gender, and I don't want to. My work, digital or analog, is very much about me and very much about being a woman.

Do you have any final thoughts or announcements you would like to share?

Yeah, I have a few things coming up!

I'm in a group show at 440 Gallery in Park Slope called ‘Eclectic Visions’ with Jo-Ann Acey and Karen Gibbons, and that's in the same space Susan Greenstein’s solo collection, starting October 12th. And then, I have an installation based on the anxiety collection at FiveMyles Gallery in Crown Heights in April 2024.

About Juliet Martin

Juliet Martin has a BA in Visual Art from Brown University and a MFA in Computer Art from the School of Visual Arts. For the past dozen years she has been a part of the fiber community, her solo shows including Ivy Brown Gallery, New York City; Chashama, New York City; Living Room, St. Peter’s Church, New York City; Sumei Center, Newark, NJ; Creative Arts Workshop, New Haven, CT; Garrison Art Center, Garrison, NY; Artworks Gallery, Trenton, NJ; and Saori Kaikan Gallery, Osaka, Japan.

Her work has been written about in the New York Times and she was named one of the “Women Artists to Watch” by Artsy. She is a member of 440 Gallery in Brooklyn. She lives and weaves in Brooklyn.

Website: www.julietmartin.com

Instagram: @remotelyjuliet