Archiving War and Memory: Katherine Akey

This is the Closest I'll Come to Touching You the Way I Want, 2021. Video, 00:10:07.

Through photography, printmaking, fiber art, and writing my work focuses on the transformation of human experience, especially that of trauma and conflict. Much of this is an exploration of the change of experience from history to myth, from mourning to commemorating. I always try to do this exploration through the experiences of individuals. Antoine de Saint-Exupery wrote that when a man dies an unknown world dies with him; photographic archives as well as personal histories, these are what is left when that unknown world disappears, these are where we can connect to the humanity of the past, these are where I excavate. My childhood was spent climbing through archaeological sites with my parents; their academic practice is the foundation of how I make sense of the world, dusty sites and overflowing vitrines that fill my memory. Now as an artist I explore history with my own archaeological tools, seeking the marks of individuals as they transform and fade with time.

Home Again, 2020. Inkjet and collage, 14in x 14in.

Can you introduce yourself?

I am an artist and historian currently based in San Francisco. I am from Virginia and Athens, Greece. My parents, professionally, live their lives out of Greece so, I spend a lot of my life bouncing between Greece and the United States. I got a B.A. in Psycholinguistics at New York University (NYU) with an interest in Anthropology and Art History. I was looking at evolutionary aesthetics, at the way human minds and brains work by looking at the development of art and literature over the course of human history.

I got to the end of college, and I realized, the only career path forward in that field was a Ph.D. My family are academics, my older brother was at Colombia University doing a Ph.D. in physics while I was at NYU and so I knew what a Ph.D. looked like. I was working at labs at NYU, as an undergrad, and I loved my classes, but I didn’t want to be a lab scientist. It was a kind of rigor, and it didn’t appeal to me and made me reconsider why I was interested in that topic (psycholinguistics).

For me it came down to this understanding of humanity, art, and creativity and I was going about this research in one particular angle. After college, I took a gap year, and applied to about a million different graduate programs. I applied to programs in Classics, Linguistics, History, Art History, Art Therapy, Creative Writing, and Fine Art. And it was through being interviewed for grad school that I settled on the International Center for Photography in New York.

Nayland Blake, who founded and ran the M.F.A. program asked if I had any questions for him. I asked, “You started this program, it’s your pedagogy, what do you want for your students?” And he said that he wanted us to be empowered to make our own opportunities and to be the art world the art world wished we were. Every other program I spoke to said, “You’re going to leave with connections, a portfolio, a robust practice…” and that sounded great, but Nayland had this different attitude about pursuing art professionally. Even though it’s this weird little program at a documentary film museum run by a performance artist, literally in a basement underneath Bryant Park (at the time), it felt like the right place for me.

After that, we (me and my husband) moved to Washington D.C. where I had a couple of different jobs right after leaving graduate school. I was teaching at the Corcoran, which is now part of G.W., I was running a community dark room in D.C., but I also worked for the U.S. World War I Centennial Commission.

I started volunteering for them, and then they hired me. I was producing, writing, researching, organizing guests for weekly one-hour long podcasts episodes. Those episodes followed our involvement in the war from the spring of 1917 through 1918. I got to talk to researchers, historians, and passionate members of the community across the country who were participating in the commemoration.

At the same time, I did a research fellowship with the Carnegie Council for Ethics and International Affairs, designed to produce new bodies of research and study about the living legacy of World War I, and how the study of it impacts our lives today. I studied a body of photographs that an American soldier had brought home from an American Red Cross hospital in France. These beautiful large format portraits were of surgical patients who received facial reconstruction, what we now call plastic surgery, but at the time was something that was being made up.

I had a baby and lived through the first nine-months of Covid before relocating to San Francisco in the fall of 2020. Now, I am mostly having a studio practice and working on teaching next year. In general, my practice is photography informed, but not photo limited. In the last four or five years after leaving grad school, I’ve expanded and self-taught fiber arts, sound art, video, and more creative writing to meet the needs of projects.

Was it your fellowship at the Carnegie Council for Ethics and International Affairs that developed your interest in World War I or were there other projects that informed your research-based practice?

Darkness Shall Cover Me, was my first solo show about World War I exhibited this year. This was the first time a whole body of work about war had been exhibited, but my interest in The War goes back to my childhood. My dad introduced me to the subject when I was younger and my thesis in graduate school was about polar exploration, comprising of archival footage that I was editing and projecting as well as displaying photograms that I had built without image-based material in a dark room.

Part of my thesis included a book which was supposed to be a summary of our grad school experience, but I didn’t do that and got sassed by professors on the review board for it. I had images from my show accompanied with one-page short stories about polar exploration and why I was interested in that subject. It was taking this approach that connected all of this knowledge and research to a more personal level.

This war stuff came after grad school. It took me from 2016 to 2020 to make Darkness Shall Cover Me let alone exhibit it. Four years was actually super quick for big bodies of work, but more forthcoming, I hope!

Forget Me Not When Far Away, 2020. Inkjet paper and collage, 14in x 14in.

Love is Sweet, 2020. Inkjet paper and collage, 14in x 14in.

Your exhibition, Darkness Shall Cover Me, investigates the first World War and night bombing. Your exhibition statement aims to look at the tension and lived experiences between bomber pilots and bombing victims. How are you exploring the rights to memory and trauma? And can you explain the significance of the materials used to tell these individual stories?

Memory is a really tough concept and by extension, history is fraught. There is a lot of ethics, theory, and navel gazing we can do about memory and history and who informs who. Memory, in psychological and neurobiological terms, is super unreliable and if we want to talk about the reality of what happened to someone, we’re not getting THE truth of the experience, we’re getting THEIR truth of the experience. It’s complicated in that sense.

I try to use first person sources as much as possible with the hope of being a channel in which these people can speak to their experiences. I’ve never experienced violence, war, not even on a personal level and I question being an interpreter for these people. So, my goal has always been to take their voice and change how it’s being presented but try to do so as undiluted as I can.

I struggle with that a lot, like my research project at Carnegie. I didn’t know if those men in the photos consented to having their picture taken, one assumes, but I have a lot of trouble using the photos directly in my art. I found it easier to use words because somehow it feels softened versus using archival photos. There are a lot of artists out there who use archival photos of trauma and are successful, but I am not sure I can do that.

That being said, this idea of memory and trauma and whose right/access is it is one of the reasons we are having this big cultural debate in the States about Civil War statues. There’s that quote, “history belongs to the victors”, “we” get to decide what events in history we are going to place value on.

These decisions, they inform who we are, what we point to, what we teach, what memorials we erect or take down, and dictate what our cultural identity and collective memory is. That is very interesting to me, this idea of something moving from the personal experience to the family experience, to a private collection, to public memory and looking at where things fall through and where things don’t.

In the context of my parents being archeologists, I would ask my dad what the greatest thing he’s found, and he always says that archeologists, historians, and by extension humanity are mostly working with negative space. What information don’t we have because it didn’t survive through time, so this transmission from personal to public memory or from trauma to mourning to commemoration to forgetting. No matter how painful the experience was to live through, it will be forgotten and the power of it will dissipate eventually. But there is value in looking at that.

When you find these first-person sources, I’m primarily getting them from institutions like the Imperial War Museum in the U.K. or similar World War I specific museums and archives, you don’t always know the context of these sources. Is this source a letter that was written to home and if so to whom? A sibling, to a parent, to a wife? Are you reading a journal that wasn’t meant to be shared? Is it a transcription from an oral interview?

Sometimes you get this information, but sometimes its not accessible in the archive you’re looking at. Going back to the Civil War statues, it is defined by who is remembering, when, and in what context. My personal experience working for the National World War I Centennial Commission, most Americans don’t have a very strong, working familiarity with World War I.

It isn’t taught very much. Either because it isn’t taught or because it’s not important to our collective cultural identity, especially when you compare it to World War II. What references can you point to about World War II? If you ask the average American about World War I, I have not experienced that someone can summon a picture or name a battle.

It is in making this work that I am trying to reconnect the context in which someone can remember these people and their experiences, I hope.

I think about it a lot in the context of photography, because although I don’t make a lot of photographs anymore, I teach photography and photo theory. I use and highly recommend Susan Sontag’s, Regarding the Pain of Others, even though it is a little outdated. She wrote her book post 9/11 but pre-Tumbler and it lacks a lot of contemporary contexts about social media and digital imagery, but the medium of photography is a really good place to go if people are interested in this discussion around ethics and memory. To frame an image is to exclude, and Sontag argues all photographs wait to be explained or falsified by their captions and what is the image without context?

Langemark 3 January 1918, 2021. Linen, logwood, linen thread, and cotton batting, 37in x 41in.

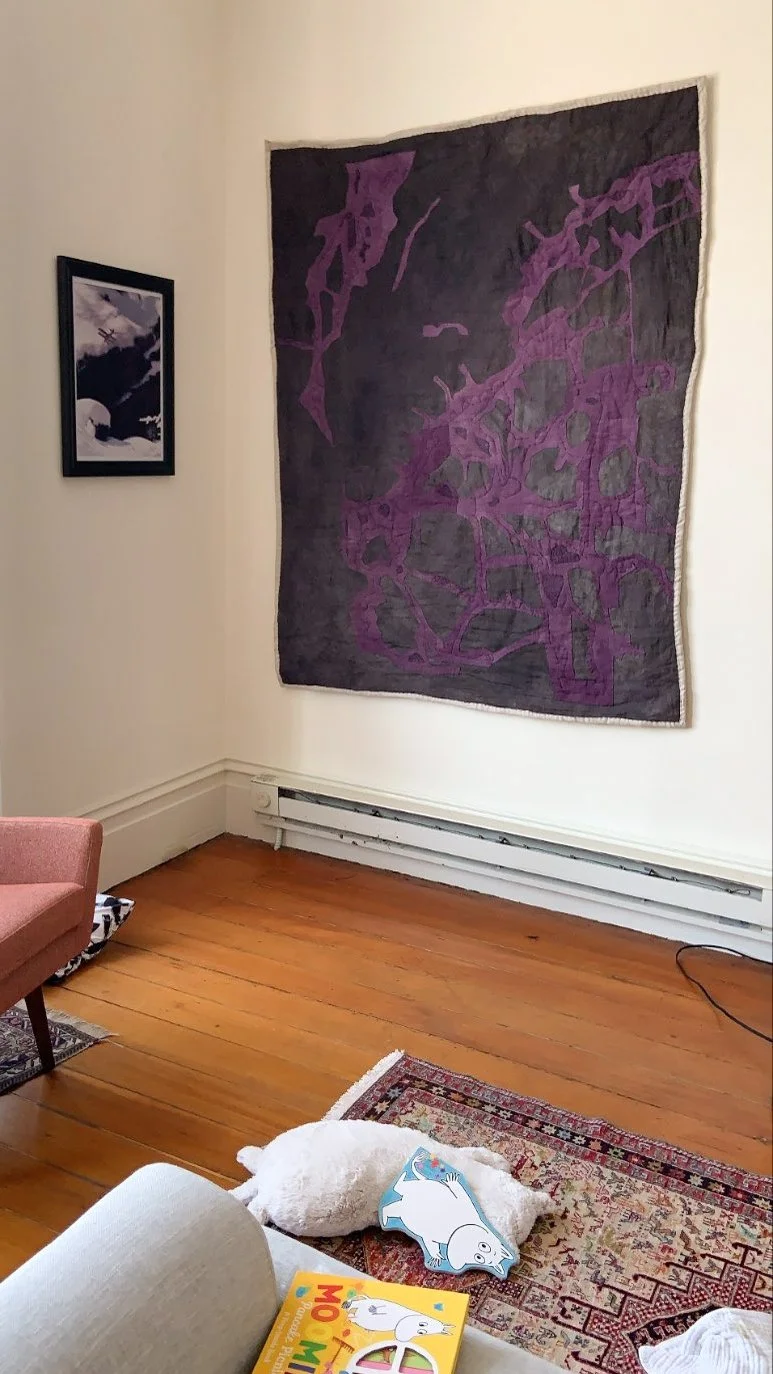

German Salient 27 May 1916, 2021. Linen, logwood, linen thread, and cotton batting, 54in x 66in.

You asked about materials, I try not to limit myself when it comes to media because of the needs of a project. Sometimes it’s difficult because you’re teaching yourself and to use that material well, you have to practice, learn, and spend money. It can be a slow and frustrating process, but I’ve tried to let the first-person source inform my choices of materials.

For the quilted pieces in this show, there was one specific story I read that informed the topic for my solo exhibition about night bombing. A Royal Flying Corps Captain and his men had been trying to do night bombing raids but were missing their targets. Planes at the time were just past being made from wood and linen, maybe still in part, and there was no electricity. The world wasn’t electrified and when you are flying at night, it is dark. This Captain described taking sugar blue paper and copying out their maps with charcoal and then he created a dark mode version of their maps. Rather than a white piece of paper with a map, it was a dark-purple-blue paper with charcoal given to pilots to memorize. And it helped them find their targets at night when flying.

This sugar blue paper, in the 19th century in particular, when sugar was transported in a party-hat shaped construction paper that was dyed. I looked up this dye, log-wood, and I really wanted to use it and that’s what colored all of these quilt pieces. I played with acidity and different metal salts to push tonality of natural dyes, but some have iron and others have copper to push it from that inky blue to a more purple, brown, and black.

The fabric is linen. In fact, it’s the same Irish linen used to make planes during World War I. Between 1415 and into 1416, planes had wood frames with stretched, starched linen. I did a ton of research to figure this out, and what I found was an advertisement from 1919. To preface, the war ended way faster than expected and the U.S. army had bought all this material and didn’t need any of it and sold it off at auctions which is where I found this advertisement for bulk airplane linen.

The quilts from my exhibit are made from the same material as the planes and it’s that process of reading a first-person source, thinking about the history, to create interpretations of aerial reconnaissance photographs from the war.

The large cyanotype pieces are made of silk and silk is another material that ties into pilots. Pilots wore white silk scarves around their necks to fill in the gaps in their cloths because their planes had open cockpits, and it gets really cold. Pilots also used the scarfs as masks to keep them from inhaling the oil off the propellers because the oil would aerosolize as they were flying and there’s no protection, so these pilots would get horrible diarrhea if they breathed too much of that oil. So those silk scarfs were used to stay warm and cover their faces.

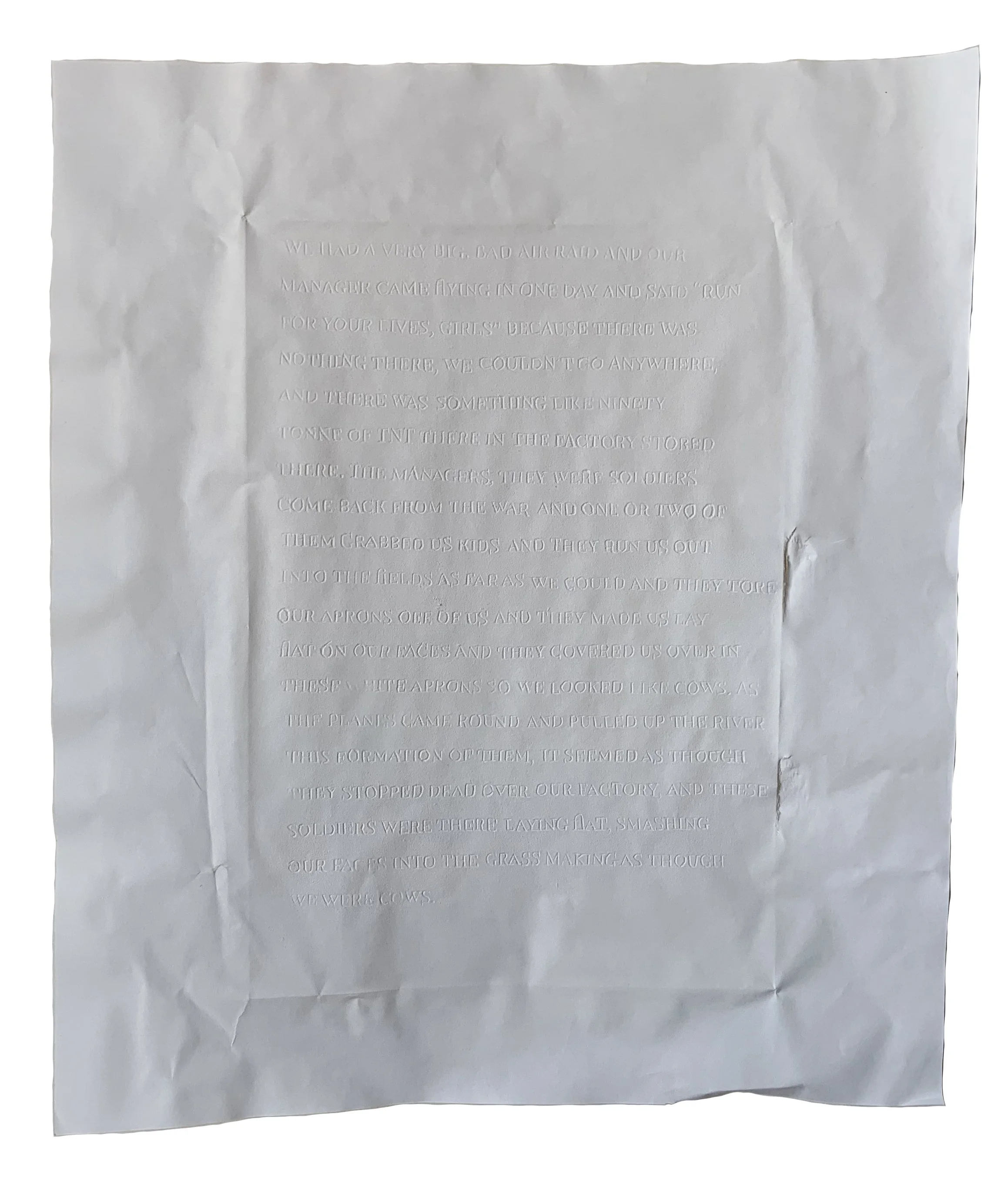

Caroline Rennles, 2020. Filter paper, 19in x 23in.

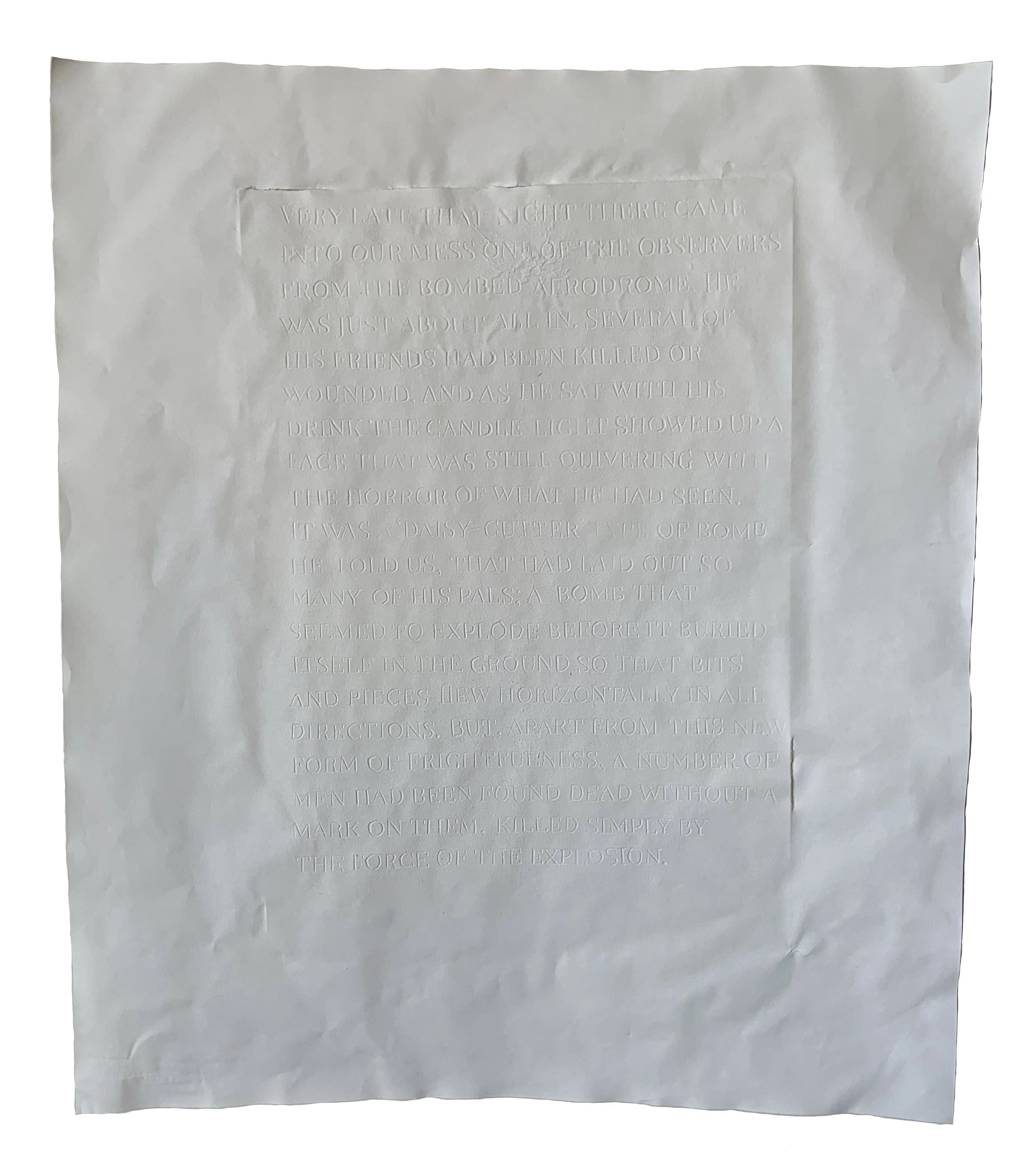

The squeezes, being witness marks, are white direct word objects that I made. Those didn’t really come from any one source; those were inspired by my dad. My dad is an archeologist and he’s an epigraphy scholar and one way that epigraphers archive inscriptions is by taking impressions. They can do this with a certain type of liquid latex, nowadays there are new methods like taking 3D scans of inscriptions, but the best analog way of doing it is to take a squeeze. It’s a scientific grade filter paper that is wet and then put up against an inscription, you slam a squeeze brush against the paper, you let the paper dry, and peel it off and bam, you’ve got a copy.

If you’re good at making these, you can see the direction of chisel marks into the stone. And you can imagine if you come across an inscription and you’re somewhere in Turkey and you can’t pick up a stone or don’t want to damage the site, this is an amazing way to make copies of an inscription to take back and study at your leisure. One of the amazing things about archives, they can protect things that stop existing. There are a lot of inscription squeezes that exist for whom the original inscriptions are gone, either they’ve been destroyed or lost.

For my trip up to the arctic, I visited the Byrd Polar Center at Ohio State University, an amazing research center for polar and arctic scientific research, and I saw their archives of ice core samples. They have these long cylinders of ice they’ve drilled out of glaciers, some that have melted twenty years ago! But we still have the ice core, so there’s this wonderful sense of bending time.

I thought this was a great way to immortalize these people’s words, the everyday experience of The War, but to make an archival collection of inscriptions that no longer exist and in fact never existed. Going back to this discussion of memorials, World War I is an interesting turning point in the aesthetics of memorials. If you think about older, traditional memorials, you think about obelisks and glory and they tend to be these very vertical, large, looming objects. Then you think about memorials made after World War I and you think about the Vietnam Memorial or the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin and suddenly everything is horizonal and sarcophagus-like, or sunken. It’s about negative space like the 9/11 Memorial at the World Trade Center is this void.

So, there’s this really big shift and yet, if I was going to make a memorial, I’d want to put these people’s words on it. Glory, death, and sacrifice are all lovely sentiments, but the words are hollow. What does sacrifice mean a hundred years later about people you have no relation to or no real contextual understanding about.

I think this is a problem with war in general and World War I in particular, minds don’t grasp horror in abstract. There are days in this war were 60,000 casualties happened. That’s a small city, but it’s not very effective in trying to get you, as a human, to understand the experience of that day.

This particular day I’m thinking about, the first day of the Battle of Somme, there’s a story I read about a man sitting in his trench and he’s waiting for the signal to go over the top and run out into No Mans Land. It’s so loud from the shells and gunfire that he’s screaming at the top of his lungs to the guy next to him. So, he grabs the guy’s hand, and they walk out together into No Mans Land. He writes home about this experience that it reminded him of walking to Sunday school with his best friend and that was all he could think about in that moment.

That’s one person out of 60,000 people, but that, I hope, is way more effective at getting you to understand what sacrifice meant in that moment. So that’s why I went to these words.

You mentioned how our memories change, especially when war is glorified, and soldiers (specifically young men) are filled with notions of patriotism and nationalism. How are you balancing those notions as a way of archiving war and memory?

Again, its about context. It’s almost unimaginable to us today, as a post-Vietnam American, to understand these soldiers willingly swarmed for conscription. There are people who committed suicide because they were rejected from the army and didn’t want to be seen as cowards. And maybe they had legitimate reasons not to fight, but this was an intense sense of duty and obligation that I don’t understand myself because of the context to which I grew up.

This war was different because it conscripted and all of a sudden, the entire population across the world were involved, which was new, but it also damaged the land and the people in a way that never happened before. It’s also the first modern war. You enter with horse drawn carriages and leave with machinery. Tanks are invented, gas warfare is invented, barbed war is applied in a military context, machine guns and bombing civilians define what contemporary warfare looks like today.

They called the Battle of Verdun the ‘Meat Grinder’ because men would enter and disappear. Going into the war, the context of the conceptualization of the British male body is very different then coming out of it. Then you get this resurgence after the war, in the 50s and 60s, and again we see the glorifying of the Tommy (slang for soldier). You have this pendulum swing over the course of the 20th century that glorifies and infantilizing and mythologizing war.

If we pull out and look at Russia, does anything come to mind during 1917? Russia collapsed! It was an empire going into the war and then you have the Bolshevik Revolution, and the country ceases to exist. And all these smaller surrounding countries begin to seek independence while millions of soldiers of all different religions, ethnicities and creeds are fighting for “Russia” which stops existing. What is their understanding of the war, their role in it, their understanding of it?

The French, being a republic, were invaded by the Germans who almost took Paris. They came miles within capturing Paris in 1914, but made a navigation error, but they were in France for the entire four years. France at the time was on the defensive and had legitimate reasons to fight, but they suffered higher casualties then a lot of the other combatants and they almost had a coup in the middle of the war. And had a soldier uprising actually happened in 1917, they might have lost the war. You can’t really overthrow your government when a quarter of your territory is an active war zone.

There was also a lot less censorship of the news and willingness to acknowledge the war, and this continued after. When you look at the U.S. or England, amputees or disfigured individuals hid themselves because the public had a lot of trouble dealing with them. In France, there is an organization that exists to this day, to promote and support wounded veterans. And its one of the largest organizations of its kind I’ve ever heard of, called Broken Jaws.

There’s this huge cultural difference in the way the war is thought about and that’s true about every war. As Americans, we’re looking at World War II and we’re thinking about it differently. Notably thinking about bombing. Do we learn about what we did to Tokyo or Dresden? We bombed probably hundreds of thousands of civilians, and I don’t think we’ve reckoned with the violence, but we’ve come to a point where we can acknowledge and integrate it into our understanding of ourselves.

Just because we were on the “right side” doesn’t mean we didn’t commit atrocities. It’s war, you’re going to go somewhere to hurt somebody, and these men accepted that. How do we deal with that as a public? I have this quote by Jane Winter, “history is not simply memory with footnotes, nor is memory just history without footnotes. The two are inexorable, braided together by public domain, jointly informing our shifting, our contested understanding of the past.”

Listening to you share these stories and hear how in depth you go in order to research a subject; I’m wondering how you mediate between self-care? And how might your work provide care to others who’ve experience war and violence in the way you’ve been speaking about?

I’m a very emotional, empathic person. When I see a sad movie, I’m sad for a week. This research does make me vulnerable, and I’ve reached a lot of points, in the ten years I’ve been doing this work, where I burst into tears. When I was researching those photographs for the Carnegie Fellowship, I spent hours looking at these mutilated faces and one day I vomited. It hadn’t bothered me for months, and then all of a sudden one photo did it.

I started to have nightmares about visiting the war front, which I haven’t done, and being blown up by an old shell. There’s an area about the size of New Jersey, in France that’s called the Red Zone, that’s uninhabitable because of World War I. Unexploded shells are still in the ground and are collected every year by farmers known as the Iron Harvest. Hundreds of tons of unexploded shells that these farmers accidentally kick up when their farming and people die!

Jack Wilkinson, 2020, Filter paper, 19in x 23in.

There’s a whole section of the military there that come and dispose of ordinance from World War I and people are still dying. I would have nightmares about going to the front and walking around with my little camera and my tripod and loosing a leg.

Whenever it gets bad, I would take a few months to disengage. In that sense of selfcare, there isn’t any because I push myself to the edge, but at the same time when I reach those points, I backed off.

You spoke to the significance of materials you use, but those materials like quilting and archiving hold specific meaning to your own life. Can you share those personal stories as they relate to your artistic practice?

Whenever I tell people my parents are archeologists, I always get this Indiana Jones reaction and in reality, it is cool. What they do is amazing, but there’s no chasing Nazi’s or hunting for treasure, they’re just researcher’s and they do it in a particular way. For a long time, I couldn’t see what an impact it had on me and how it framed my understanding of the world.

I’m one of four kids, and I’m the only who thinks about history. My youngest sister is a florist, my other sister is a physical therapist, and my brother is a physicist but none of them are thinking about history and art. But it did make us appreciate history, culture, craft, time, and objects. Plus, we got to grow up traveling.

My stepfather, who’s the archeologist, is from New England and that’s been an influence in my life as well. We’d spend a couple of weeks on Nantucket where he had his summer home which is a very unique environment. It has its own history around whaling and the arctic that I’ve drawn on for my residency.

My biological father was a navy brat, whose father served on submarines for 30 years, and he grew on navy bases in Guam, in Spain, and all over the place. And his life has its own legacy that bring influence.

My mother, who I spent most of my life with, is Appalachian. I’ve counted the generations before, and we think I would be about 14th or 15th generation. That part of the family got here in the 1700s and went immediately to West Virginia and stayed put in the mountains. That’s unique in that there’s a subset of Americans who can trace their family back to the 1700s and that my family was in one place for so long and its such an interesting place in terms of culture and craft and tradition.

My grandfather is that last person in my direct line to live in West Virginia. At this point, when my grandfather passes, we will have broken a three hundred plus year old chain of living in the same holler (what we call valleys in West Virginia). And that is a weird and intense thing for us to make sense of and no one wants to go live there, no one wants the farm, and we’ll probably end up selling it and that’ll be that.

I have been photographing my grandfather and the land trying to reconnect with some of the culture and craft knowing that that connection has a timer on it. Which is where something like the quilting comes into play. I learned to quilt when I was a very young girl and is super important to Appalachian home life. Everything is a practicality and a craft second, but its also an art form and people took a lot of pride in, especially my great grandmother. I love the reuse of cloths into quilts, I’m actually sitting here with one of my great grandmothers’ quilts that is made out of my mom’s dresses. My dad loves this quilt because it has a number of pieces of cloth from dresses he remembers her wearing when they were first courting each other in college. What a piece of history, right!

I named my daughter after my great grandmother, and I have pictures of her as a baby sitting in a chair draped with a blanket my great grandmother made out of my grandfather’s cloths and here’s my daughter posing on it and sleeping with it.

The root of all of these crafts is about survival, no one at the time was educated and my grandparents in the 40s and 50s are the first people in my family to make it past 8th grade. My grandfather went to law school and became a lawyer. His daughter went on to become an archeologist and do fieldwork in Greece. That’s a huge jump in just two generations!

I’m trying to be more appreciative about the craft and bring it into my practice. Those quilts were a good opportunity to do that. I don’t think they read as quilts, certainly not in the traditional sense, but the application of skill is there.

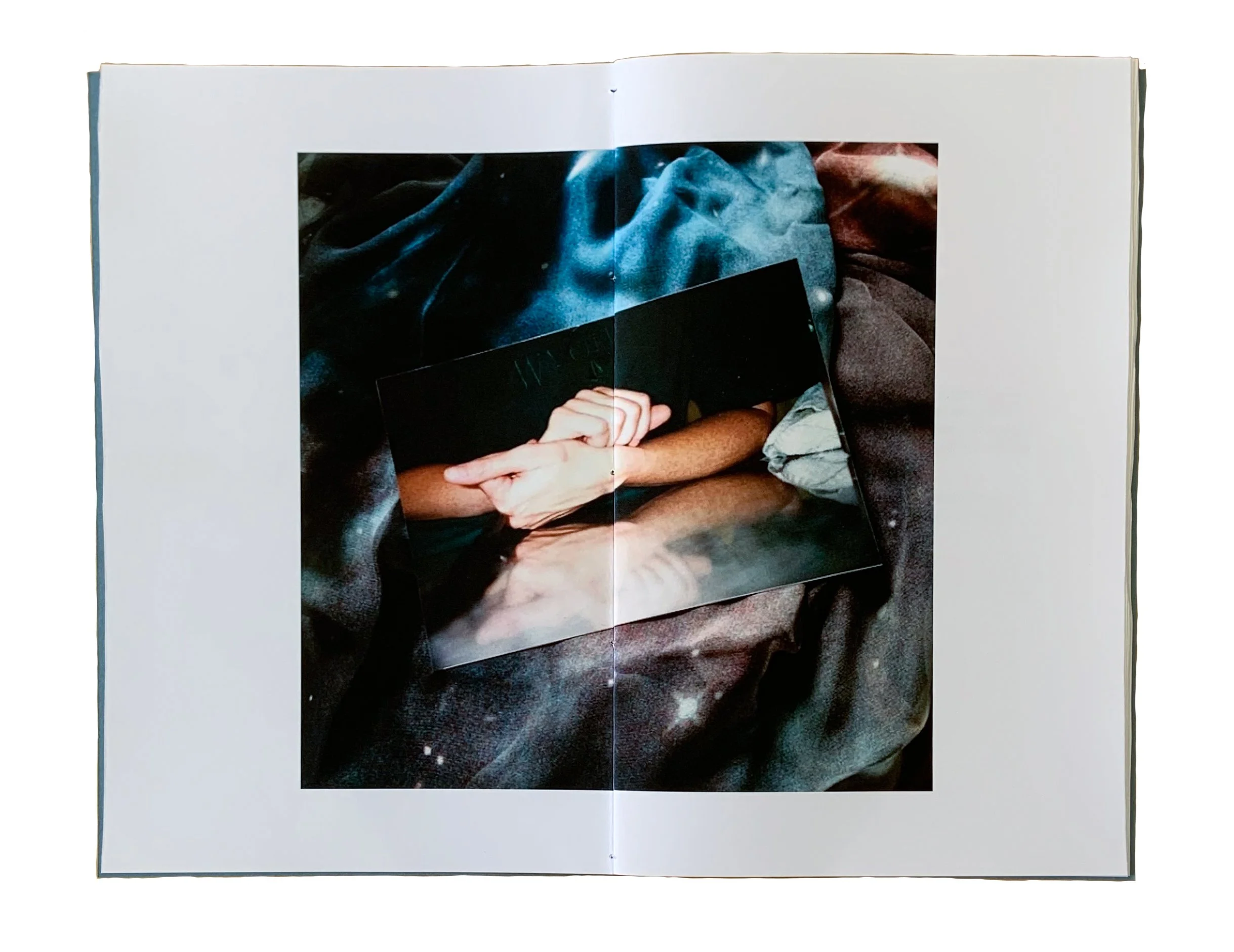

Mothers' Hands, 2021. Inkjet prints, paper, and linen thread, 16 page book.

As a new mother, you shared the difficulties of balancing an artistic career and a newborn and the importance of having resources like the Artist Residency in Motherhood. Can you share your experience with that program and how your worked has evolved?

Having a kid is the most profoundly transformative experience. I had my daughter four months before Covid and my experience as a mother is entirely colored by the pandemic. And I think there’s going to be a lot of writing and researching about what that does to us as parents.

That time as a mother and an infant is valuable and space should be made for it, but we don’t think about it in that way in America. I went back to work five weeks after having my daughter. I had a C-section, and I was hurting when I went back to work but I felt obligated! I had that pressure to do it all and one of those pressures was joining a residency to force myself to keep making work.

The residency was started by Lenka Clayton after she had a child and it’s a D.I.Y. residency. She provides a contract that you go through and fill out, answering questions like where am I, what are my needs, and how do I hold myself accountable to meet these goals. And you design your framework for you to work within. It gives you time and space to make it what you need and what you can fit in.

I decided I was going to start in the beginning of March 2020. Two weeks into March, I was trying to teach three fine arts classes via Zoom while trying to breast feed off camera. That residency didn’t happen. I couldn’t tell you now, if it was postpartum depression, was it Covid, an existential crisis but I was a mess. I was nonstop crying, my hair was falling out, no sleep and it felt like the lowest point in her infanthood that June/July. I couldn’t make any work because her studio was her nursery, but she was home 24/7 and I was freaking out that my career was over. I went back to the contract for the residency I failed to start, and I realized what I needed was a break. I need to give myself permission to not make work.

After that we relocated to San Francisco in September 2020 and that provided me with a separate room for my studio and provided us with safe, close childcare which we didn’t have in D.C. My daughter was older at that point and her reliance on my body changed and I eased myself back into the studio. It felt really overwhelming to start anything big and so I asked myself, what can you do that’s bite sized?

I wanted to make something about motherhood, one thing about quarantine, and one thing out of the archive. I had this book about my grandfather that I had started in 2017 and I never found time to print or finish. And so, I finished it. Just that was like breaking the dam.

I made another book about our daily quarantine walks around our new neighborhood and then I made another book about my mother, me as a mother, and me as a daughter, and my daughter. They’re little sixteen-page books, mostly photos and a little bit of writing. They didn’t have to be amazing, but it gave me the confidence to get back into the rest of my work.

You are currently working on a new project exploring the flora from the war. I am really interested in this project because it makes me think about how war is about occupying land and changing the physical landscape. Are you interested in making the landscape the subject in your work? If so, what themes are you exploring and how do you hope viewers will interact with the landscape as it relates to memory?

Do I want to make the landscape the subject, no.

Full disclosure, I’m really early into this project but I don’t think that’s where my interest is. There are a lot of different landscapes and a lot of different experiences of the conflict. There are these stories where men talk about flowers and birds.

I will say, I have a very Anglo-centric research practice so far and have been mostly talking about British men and less about the French and Germans. This is something I really want to work on, but the language barrier has been a huge problem despite reading French quite well, I’m just struggling with access.

This project is about these people and their relationship to the environment they’re living in. There are some stories in that mud and blood landscape, a gunner writes in a letter home about a little creek and this creek is where he goes to shave his face in the morning. But in the creek, its several years into the war now, there is a human rib cage and it’s been totally skeletonized and catches all the leaves and sticks and muck. On the other side of the rib cage is very clean, clear water and this is where the gunner goes and fills up his cup and shaves his face, right at the edge of this human rib cage.

That is a psychopathic thing to say in such a flat affect, but it really tells you about what living in that landscape was like.

The bird thing is heavily informed by the British. They have this real affinity for bird song and the idea of the bucolic and bird watching. Foot soldiers would write home, in incredible detail, about the kinds of birds they saw and if they were similar or different than the birds back home. And these letters were sent to bird periodicals that were published in England.

I did this little sound piece about nightingales, but there’s this soldier who talks about the barrages and the first thing you’d hear after the barrages ended were nightingales singing. And that reminded me of a story from England where this famous cellist, Beatrice Harrison, who was practicing outside in her garden one evening in the summer, heard a nightingale singing along with her cello. She told a friend about it who loved it so much that they went to the BBC radio, and they decide to play her, and the nightingale live over the BBC radio.

The British loved this, and they keep doing this broadcast for decades after. Eventually Beatrice isn’t there, but they keep broadcasting a nightingale from a garden. And I had this realization, you’ve got World War I veterans, about half a million, who go home to England and sit there every spring and listen to the nightingale sing and there’s probably a few that remember hearing the nightingale after the barrage.

There’s this instance in World War II where the broadcast was supposed to happen, but a raid was leaving to Germany and the BBC decided to not broadcast because the Germans could listen for the positions of the planes via the radio. But they recorded it onto vinyl and so we have this recording of the nightingale, and you can hear the planes leave and then you hear the planes return, eleven fewer in number. So, there’s this loop between both World Wars and with this bird. That’s really cool.

They had gardening competitions during the war. You’d be up in the front lines for about a week and then you’d get rotated back to a village and you’d get to rest and then go back to the front. And so, when they were off the lines, they had these amazing vegetable and flower gardens, and they’d write home asking for seeds. And its just incredible they were doing this as a means of survival and enjoyment in the middle of this conflict.

So, its stories like that that I’m thinking more about coping in this environment rather than the landscape at large.

Do you have any closing thoughts or announcements?

Yeah! I’ve got a video piece from the arctic that’s about love and longing and being separated and explorers and whalers and that’s going up in a film festival in Copenhagen in the New Year. I have an audio piece about the nightingale, which is titled, War Comes to the Nightingale, that’s going to be apart of this really awesome project called Future Nostalgia FM which is a sound and radio based curatorial project. The audio will, in part, be presented in a traveling kiosk around Germany but also all the pieces included will be broadcasted on a dedicated radio station for the next thousand years.

I’ll be teaching some classes at the Penumbera Foundation. The first one about writing and photography and then later in the year, hopefully, one about art and motherhood. Other than that, I’m here in the studio trying to grow plants for this new project, doing my reading, and working on what’s next.

About Katherine Akey

Katherine Akey is an artist based in San Francisco, CA. Her work addresses adventure, conflict, and the negative space in personal and collective memory with a focus on polar exploration and the First World War. Her practice includes photography, printmaking, fiber arts, and creative writing. She has an MFA from the International Center of Photography, was a Fellow with the Carnegie Council for Ethics in International Affairs, and teaches photography and art theory.

Website: www.katherineakey.com

Instagram: @katherine.akey