Breaking Oriental Tropes︙Ye Xuanlin

Vase and Flower, 2022

Mixed media

48 x 72 in.

Breaking Oriental Tropes︙Ye Xuanlin

My artistic practice delves into the complex tapestry of intertwined themes and historical legacies, weaving a narrative that explores the intricate connection between Asian American personhood and the rich heritage of Asian art traditions. Drawing inspiration from diasporic objects that reside in Western museums, my paintings serve as a platform to recontextualize, interrogate, and unravel the layers of colonial legacy. Through the physical manipulation of paint, I take the imagery of traditional Asian tropes and question them on the canvas in a humorous or insouciant way.

As a painter, I use my creative process to interrogate and reflect upon the complex nexus of the image's origin, its historical and environmental contexts, and the formulation of artistic visual language. I frequently paint on top of photo-transferred images to manipulate, alter, and comment upon the image's cultural content. This act of painting becomes a reconstruction of the narrative of the painting itself, in addition to the allegories contained within, while serving as a deconstruction of the meaning of photo-transferred images. The painting process raises many questions for me as an artist, such as: How are images culturally conditioned? How does history help form images? What is the tight-linked relationship between my identity as an artist and the subject matter that the audience expects to see?

By subverting established visual tropes, my work challenges prevailing narratives and invites viewers to critically engage with the cultural implications embedded within the imagery. Through humor and playfulness, I seek to dismantle stereotypes and spark dialogue surrounding the multifaceted experiences of Asian-Americans in relation to historical aesthetics and contemporary society. With each brushstroke and choice of materials, I aim to dismantle stereotypes and reclaim agency for Asian-Americans, offering a compelling visual commentary on the entangled intersections of history, aesthetics, and sociocultural dynamics.

Welcome Ye, can you tell us a little bit about yourself?

Hi, My name is Xuanlin, I am a painter, art historian, and art educator currently residing in Chicago, Illinois. I specialize in exploring images with rich cultural contexts and questioning their meanings through editing and experimentation in my canvas. My work often incorporates traditional Chinese elements and reinterprets them in a contemporary way. By manipulating and transforming these images, I aim to create a sense of tension and invite viewers to reconsider their understanding of cultural symbols.

Water Lily Pond, 2020

Oil on photo transferred canvas

12 x 12 in.

Ornament Flowers, 2022

Mixed media

10 x 8 in.

In your artist statement, you write about many themes of identity from your own diasporic experience to the Western fetishization and whitewashing of Asian identity and history. How are you thinking about these themes in your painting practice?

In a recent conversation with my partner, she pointed out that my painting, in essence, is a form of self-constructing as a method to collage my experience in a 2-dimensional space. I come from a small town in China called Wenzhou, located in the south of China near the Sea. Geographically it's surrounded by hills and mountains and has no land to farm, so historically the people of Wenzhou have been encouraged to leave, and relocate abroad. Many of my relatives have relocated to other cities or live abroad. So this experience of living outside of Wenzhou becomes a generational experience. The idea of running from the land in which we are born, becomes common knowledge. I think that has something to do with my painting, you know, I came to the US when I was 19, and went through a transformative experience of like receiving this American education, and then having lived here for so long, I guess, I needed a way to really construct my own experiences and identity through my work. So, I wanted to resonate my personal experience with themes such as "western fetishization" and "white washing of Asian bodies." I'm thinking about how those themes are part of the whole experience, and then me as a container. Like incorporating these themes into my paintings is just one aspect of the whole experience.

Do you see the Neon?, 2023

Mixed media

10 x 8 in.

Porcelain Fragments, 2022

Mixed media

10 x 8 in.

How are you creating points of entry for the audience to engage in dialogue with your subject matter? Is it through artwork titles or descriptions?

I think the entry point for my work is often the visual itself, although, there is so much personal experience and thoughts behind all the work. I believe the work itself should, at foremost, be visually interesting and create a sense of aurora to invite my viewers to look at my work. Then, if people are interested and they start to look into the painting, they start to see those more complex questions.

I wanted to create a space where the viewer can challenge themselves where their preconceived notions of whatever the imagery means for them. But I think that work should challenge, and if they read more, that ‘ah-ha!’ movement is also rewarding.

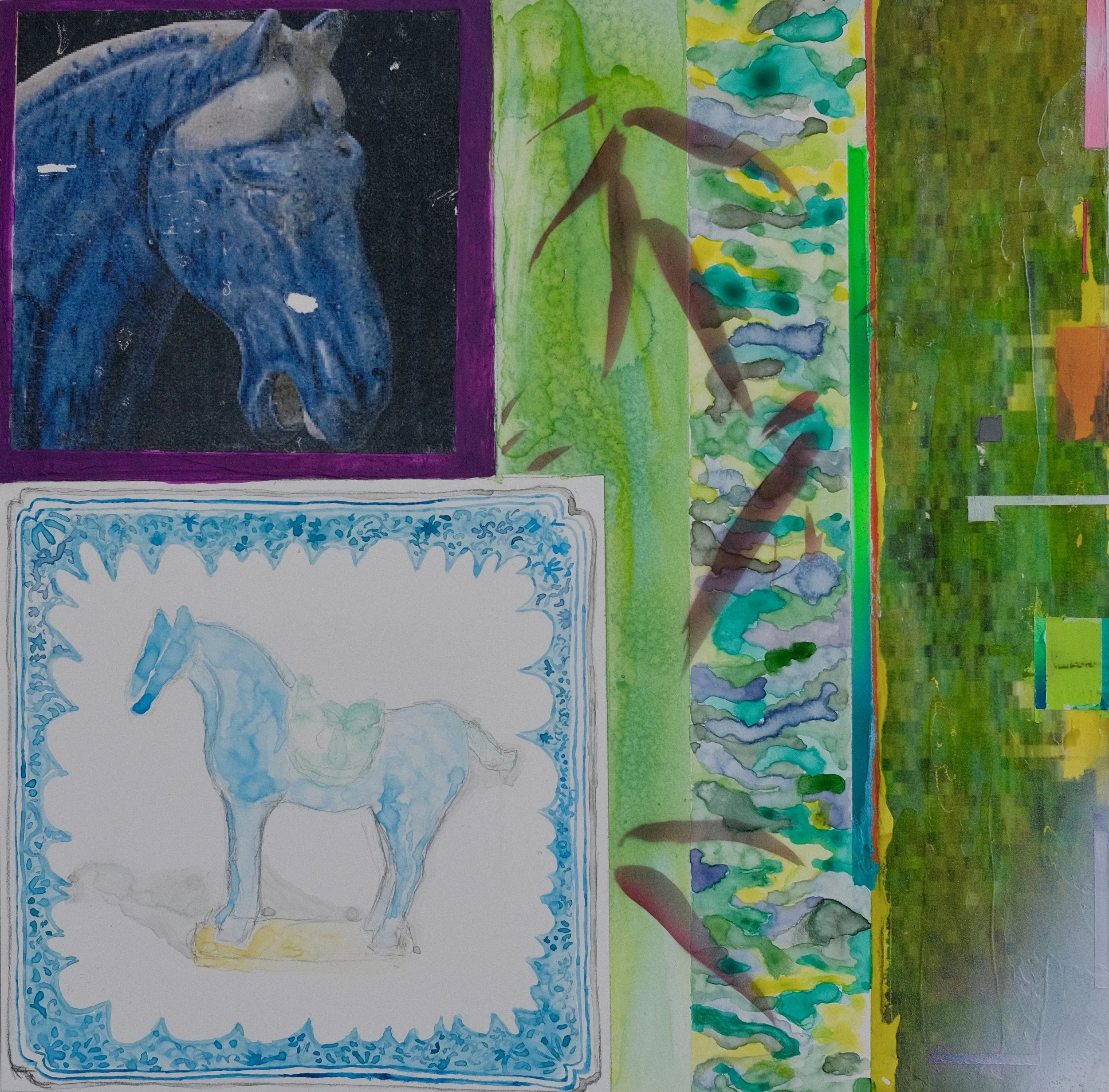

Untitled (Gold Leaf and Horse), 2022

Acrylic, photo transfered, gold leaf

18 x 24 in.

Do you incorporate Western iconography to challenge or create tension in your work?

Yes, incorporating Western iconography in my painting is one of the ways of play in my work. I really enjoy using those iconographies in my work as a way to create a sense of tension or using them purely as a visual device in my painting.

For example, in my painting “Untitled” I photo transferred an image of a blue horse from the Nelson Arkin Museum of Art’s Chinese collection. Then, at the bottom of the painting, I cut out a silhouette of a man riding a horse, running. The image is from the 1878 American photographer, Eadweard Muybridge, who made the first moving image. In a sense, it was also the first GIF.

At the time, I thought there was something very interesting between the dichotomy of one image that marks the technological innovation of mankind, and one image of a horse sitting in a museum in America where it's original purpose was to be entombed in the ground with the hope that someone can ride the horse into the afterlife.

You talk about notions of “orientalism” being woven into American culture. Can you explain what you mean and how you are reclaiming the visual imagery of Asian art?

I think I should explain what "orientalism" as being woven into the American cultural fabric means for me.

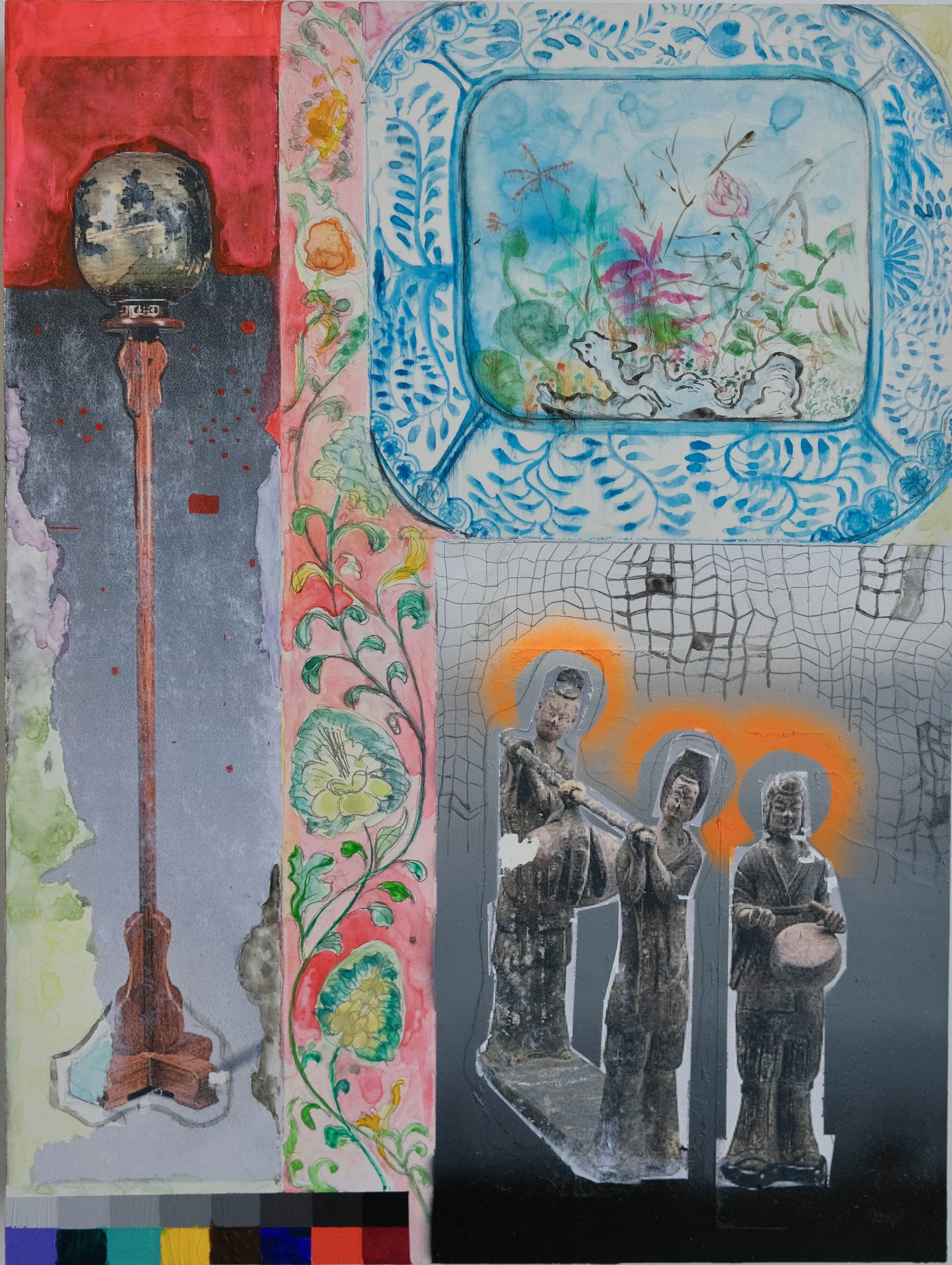

From the 1800s, porcelain was a material craved by American consumers due to the difficulties of travel and also China's strict travel policy set by the Qing court. Porcelain became a surface of imagination for the Westerner, and the goods from this land of “otherness” became very rare and highly fetishized. So from the very beginning, China and “Chineseness” were closely linked to an exoticized “Other.” And from this mentality and cultural condition many images are made to be used and to be consumed by this culture of “orientalism.”

And for me it's very interesting to embrace those notions and ideas and use those imagery in my painting.

Blue Horse, 2023

Mixed media

10 x 10 in.

For many artists of color, there is an expectation for one’s artistic practice to “play up” to their identities, oppression, and histories. How are you navigating the “racial performance” when presenting your work and discussing themes of belonging and place in the art world?

During my early artistic career, I was still in this exploratory mode. I was struggling to find a way of painting that was truly representative of who I am. I made a large painting that is similar to early abstract expressionism with a ‘zest of zen’.

I received a lot praise for the painting, however, I was not really pleased with it because I thought it was a painting that reflected on my stereotyped understanding of modernized Asian landscape painting. The praise from my classmates and professors only made me more suspicious that my painting represented their mystic Oriental trope rooted in the colonial-era cultural understanding. The painting I had made was influenced by the artists Zhang da Dian and Zhao Wuki, who were both working in the 1950s with a similar goal to modernize the Chinese painting, but I was also influenced by Western abstract expressionist artist.

I look back now, and I really appreciated those moments of my audience responses and my thought process at the time. I think yes, as an artist of color, we feel like our artistic practice should play up to our identities, oppression, and histories. But I feel that through those lenses, I am able to discuss very specific topics within my human condition. I am deeply concerned and curious about the corporal experience of the yellow body in the West. It was not long age that eight women were brutally murdered in a massage parlor in Atlanta, and even a couple of weeks ago a Chicago man, while traveling in Germany, sexually assaulted and murdered an Asian American women in a tourist spot. I wonder, ‘what does it mean to be viewed as hyper-sexualized, yet at same time, be desexualized?’ ‘What does it mean when my flesh is turned into an object, and the object of my culture is both appreciated yet tainted with all kinds of ideas?’ I try to not bring in too much emotion, but to peek in as an observer, and to use my canvas as a way to take apart small symbols and really question, ‘how does this imagery look at both by my peers and the public? And ‘how does the imagery function for them, and how does it function within my painting?’

Your practice reminds me of the Filipino artist, Stephanie Syjuco, who creates parodies the imperial museum and looting practices that make up the foundations of Western collections. You also use museum collections in your work, and so what kind of museums do you seek out and what type of collection do you gravitate towards?

I think both of us are very interested in the symbolism of images. I was also watching her interview a couple day ago, I feel artist who are going through this legal process of visa and immigration often have big impacts on thier work. The idea of being a legalized body seems so black and white, and as an artist, it’s inevitable to question and wonder about the degree of the grey and who I really am in the process.

When I go to museum to visit an Asian art collection, I really enjoy the paintings and ceramics. Sometimes I try to look at stuff if there are interesting patterns and unique motifs that I can incorporate into my own work. I went to the Nelson Arkins Museum of Art a couple of months ago, and they have this wonderful life sized Guanyin sitting in front of a Buddhist themed mural. Having studied those objects with specialist, Lin Weichen at the University of Chicago, I finally understand the weight of those histories these objects hold. I was wondering, what it means to have a temple taken apart piece-by-piece, cut up block-by-block, and then transported to another side of the world to be installed for display.’ Sometime I wonder how the Guanyin feels, to be a God in a land where she supposes to be worshiped, now merely an object of beauty sitting very still in a museum space. Within the museum there’s a certain aura of time. What I want to do is bring an object out of the museum, already without context and reappropriate it into my paintings to address the object in a way that tries to give back more context.

The first step is usually sketching, and then finding an object that I want to bring into a painting. Then I do this layer of photo-transfer and that becomes my subject which creates a lot of interesting problems for me. Although the initial sketch my take you somewhere, it might only take you to a certain level of place. Sometimes the painting just doesn’t work out and you have to reinterpret the subject again to see how the painting functions. So that’s where relationships need to happen between the object as historically significance, but also as an image within my painting.

You also write that museum’s Asian collections are diasporic. Can you explain more and what specific motifs or icons you use that speak to that?

Interestingly, when I am searching for imagery, I try to avoid imagery with too much cultural context because it is very difficult to work with too. That the viewer’s understanding of the work is limited by that sometimes. I still know where the object is from, but I also want to have this hint of the origin of the object because I think there’s a really fine line of ambiguity and level of specificity. I’m using those images as pictorial devices to drive my paintings further.

When I talk to my Asian peers, many of them try to go back their roots in their practice. But going back to their roots is so complicated, because if I do something “zen” it’s already so tainted with so much connotation. I have to address a very specific question that’s happening in the US, like how those themes are being seen? So in that way, I’m being pushed towards a new frontier in reclaiming imagery in my work.

Blue Vase, 2022

Mixed media

16 x 12 in.

The Welcome Procession, 2023

Mixed media

9 x 12 in.

I imagine that you have two types of viewers: people within your community with similar identities and understanding of your work, and those who are not. Who do imagine your viewer being, and how are you reaching out to those who might not understand the themes of your work?

This is a great question!

I also think there are two type of the viewers, but most of time I assume they arrive to a similar understanding of my work. Even if they have a different understanding of my work, I think what my job is, as an artist, is to nudge my audience to see the work as they have never fully realized before. I want to have my work speak for me, even to those who are outside of my cultural background. I want my work to challenge their preconceived notions of those images and materials that appear in my paintings. And for those who have a similar background, I also want use my painting to challenge their fixed understanding of their lineage and cultural understanding.

The challenge is that paint exists on a 2-dimensional surface. As a painter, I think that if the painting is visually interesting—it’s painterly, it makes sense—but also has that layer of push-and-pull relationship then you’ve defined the obstacle. Once the painting already functions at the level its supposed to be functioning, then where ever my viewer’s level comes from, they’re already having a very interesting play with the painting.

Do you have any final thoughts or announcements you would like to share?

I don’t, I wish I did!

Aubade of Sunken Flower Vase, 2023

Mixed media

12 x 12 in.

About Ye Xuanlin

Xuanlin Ye works and lives in Chicago. He received his BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago (2017), received his MFA from Hoffberger School of Painting at Maryland Institute College of Art (2020), and graduated from the University of Chicago with an MA in Art History (2022). Ye completed his thesis under the guidance of renowned art historian Wu Hung. He is the recipient of the Hoffberger Fellowship and MFA Juried Exhibition in Print by New American Painting featuring one issue #159. He has been exhibited around the world, including Still, life at Art Cake Brooklyn, NY (2021), and has been featured at the Asian Students and Young Artists Art Festival at Hongik Museum of Art in Seoul, Korea (2021). His work was exhibited in art fairs, including Art San Diego(2022) and the art expo Dallas Taxes (2022), and the MDW art fair in Chicago (2022).

Website: https://www.yexuanlin.com/

Instagram: @yexuanlin

Interview by Zoë Elena Moldenhauer